Mental Health Check

According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, “mental health means striking a balance in all aspects of your life: social, physical, spiritual, economic and mental.”

According to the Canadian Mental Health Association, “mental health means striking a balance in all aspects of your life: social, physical, spiritual, economic and mental.”

It is hard to see a person’s psychological, social, and emotional well-being. And that is what this project is all about: what you don’t see.

Most people have been affected by mental health either personally or through someone they know. Because it is such a widespread issue, this topic can never receive too much attention.

Although, recently, more conversation has been generated about mental health, we still have a long way to go. As few as one in three people struggling with mental health may actually seek help. Suicide has become one of the leading causes of death between the ages of 15-24. And millennials have the highest levels of clinical anxiety, stress, and depression compared to any other generation at the same age.

In this project, we explore the relationship between social media and self-worth, the cost of mental health treatment, and the alarming suicide rates among millennials. We want to examine the issues, talk about some initiatives that could help, and keep the conversation going.

Number of millennials in Canada with mental health issues

Behind the Smile:

Inside the Millennial Mind

Body Image

The body image of most millennials’ plays a large role in how they present themselves and, more importantly, how they feel about themselves.

Media Impact

The media and social media heavily influence millennials in today’s world. Often, the media influence is not a healthy one and leads to skewed perceptions.

Costs

Money is another factor that impacts millennials’ mental health. The cost of treatment can be high and the wait times for public health services long.

Suicide

Unfortunately, when pressures become too much, some choose to travel down the path of self-harm, which often leads to suicide and lives cut short.

How Do I Look?

What do you think when you look in the mirror or picture yourself in your mind? Do you feel confident? Body image is strongly connected to one’s mental health. A negative perception of your body can lead to many mental health issues such as anxiety, depression, anorexia, and Body Dysmorphic Disorder (BDD). In this section, we are going to look at body image from the perspective of mental health, including eating disorders, cosmetic surgery addictions, and how your relationship with food impacts your relationships with other people.

Eating Disorders

Eating disorders are often characterized by unusual eating behaviours and distorted views of food. They typically occur during adolescence and young adulthood affecting both men and women, but are more common among women.

Eating disorders are often characterized by unusual eating behaviours and distorted views of food. They typically occur during adolescence and young adulthood affecting both men and women, but are more common among women.

Dealing with body image is difficult and openly discussing body image on a public platform can be very challenging. But after reaching out on social media, we were surprised when numerous students agreed to share their stories for our project. Here, we highlight Sydney and Samantha, two young women who bravely open up about their personal struggles with body image.

Body Dysmorphic Disorder

Low self-esteem, obsession with one’s self image, constant self comparison to other people and extreme dieting could be a red flag of a mental disorder known as Body Dysmorphic Disorder or BDD.

According to the Mayo Clinic website, BDD is a mental disorder where a person becomes obsessed with flaws in their appearance. These are flaws that others don’t see but someone with BDD becomes fixated on them to the point that’s all they see. Experts say BDD is one of the main reasons for cosmetic procedures in early adolescence and teenage years.

In her article for Our Bodies Ourselves Diana Zuckerman, president of the National Centre for Health Research in Washington, says “…in 2015, more than 226,000 cosmetic surgeries were performed on patients between 13 and 19 [years old], including nearly 65,000 surgical procedures such as nose reshaping, breast lifts, breast augmentation, liposuction, and tummy tucks.”

The American Board of Cosmetic Surgery (ABCS) identifies that cosmetic surgery and plastic surgeries are not the same. While both techniques deal with improving a patient’s body, the procedure and the reasons for getting it done are different. Cosmetic surgery is a choice made to improve a patient’s appearance. Plastic surgery is often a necessity, used to reconstruct body defects caused by birth, accidents, burns, or diseases. But, all cosmetic surgery originated with plastic surgery, as outlined in the timeline below.

Although BDD can be easily mistaken for narcissism (a personality disorder where one becomes obsessed with self), there are a few things to look out for to detect BDD. The list below is an abbreviated one from the Mayo Clinic:

- • Strong belief that you have a defect in your appearance that makes you ugly or deformed

- • Belief that others take special notice of your appearance in a negative way or mock you

- • Engaging in behaviours aimed at fixing or hiding the perceived flaw that are difficult to resist or control, such as frequently checking the mirror, grooming or skin picking

- • Constantly comparing your appearance with others

- • Having perfectionist tendencies

- • Seeking frequent cosmetic procedures with little satisfaction

- • Avoiding social situations

- • Being so preoccupied with appearance that it causes major distress or problems in your social life, work, school or other areas of functioning.

Can I Afford This?

Fifty billion.

That is the enormous sum drained from the Canadian economy annually by mental illness. Enough money to provide a solution to homelessness in Canada, and leave a few billion over. Enough to put a massive dent into the country’s poverty crisis. However, the drain extends far past the nation as a whole, it reaches the bank accounts of those suffering. Treatment for the mentally ill has been referred to as a two-tier system, and those unable to afford the costs of therapy and drugs are left behind. How will Canada’s millennials deal with an institutional crisis that is reflecting on the economy and their health?

Canada is facing a two-headed mental health crisis that remains in the dark. More than half of young adults in Canada report facing depression and other mental health concerns, far exceeding previous generations. Exacerbated by anxiety over their job prospects, and living costs that continue to balloon year by year, the stress is taking its toll on more than the minds of millennials–it’s also impacting their wallets. Money is increasingly becoming the key to successful treatment.

Canadians in the low-income bracket are three or four times likelier than the high-income bracket to report poor to fair mental health. And as reported in the Toronto Star, millennials without the financial means to support their condition encounter what mental health advocate Michael Kirby calls, “a two-tier system of care for children and youth needing mental health services.”

The road to treatment remains a challenge for many. In Ontario, wait times for treatment from a psychiatrist range from two weeks to two years, putting the health of thousands of youth in the balance. Bypassing the public system for swift relief is possible, but only for those who can afford it.

The Ontario Psychological Association in 2013 set the cost of hourly treatment at a recommended $225, which is an expensive sum to shoulder for many families and individuals.

Dr. Sylvain Roy, President of the Ontario Psychological Association, says, “You can be connected to a psychologist almost right away if you can pay or have private insurance. The advantage of being wealthy is that you don’t have to be on a year-long waitlist in hospital for mental health care.”

But more than anything, Dr. Roy says the problem lies with how mental health hospitals lack individual psychotherapy: “There are extremely long waitlists. You will be lucky to have access to group therapy.”

Not to mention the price of the drugs, which many rely on for treatment. Without insurance, drugs like Prozac and Cipralex will cost $80 for a 30-day dose. Over time, that cost accumulates–a healthy life has a price tag attached to it.

Millennials of Canada bear the brunt of this two-tier system. Left with limited resources and options, mental health treatment has become a privilege, rather than a right and it doesn’t get easier when they transition from youth to adulthood. Dr. Roy says, “When these youth become adults they struggle to get the care they need. We must remember that there are mental health services gaps for all Ontarians.”

Partners for Mental Health is an organization that is trying to fill those gaps. It has helped over 400, 000 Canadians with the Not Myself Today campaign. The initiative provides employers the knowledge to support workers through mental health struggles. The recent uptick in conversation surrounding other campaigns, such as Bell Let’s Talk, has been instrumental in Partners for Mental Health and Not Myself Today’s goal of stigmatizing mental illness. PJ VanKoughnett-Olson is a Director at Partners for Mental Health and shares why it’s so important for businesses to take an interest in employee mental health.

What's the Point?

Sadly, sometimes the mental anguish felt by millennials becomes too much, and they choose to end their own lives. According to the Canadian Mental Health Association (CMHA), suicide is the second leading cause of death among Canadians aged 10-24. Looking at marginalized groups, the stats are even more alarming: the rate of suicide among Aboriginals is almost twice the national average, and a study conducted in Manitoba and Northern Ontario found that 28 per cent of transgender and Two-Spirit people had attempted suicide at least once. Many youth struggling with mental illness self-medicate with alcohol and drugs. In this section, we’ll delve into why youth consider suicide and what ultimately makes them ask, “What’s the point?”

Indigenous Crisis

The suicide rates in Indigenous communities are astronomically higher than they are among non-Indigenous youth. For example, among Inuit youth, suicide accounts for 40 per cent of deaths (compared to 8 per cent in the rest of Canada). According to one study, suicide rates are closely linked to “cultural continuity,” which it defines as a community’s self-governance, involvement in land claims, and more. Young Indigenous Canadians face unique challenges.

We’d like to introduce you to someone we’re going to call Mary. We’re using that pseudonym in order to protect her identity. Mary grew up in Pikangikum, a remote reserve in northwestern Ontario. In 2012, Macleans Magazine called Pikangikum the “suicide capital of the world” and Mary herself has attempted to take her own life more than once. Click on the letter to your left to get her first-hand account of what it’s like to live on the reserve where addiction and isolation go hand-in-hand, but where there is also astonishing beauty and a rich culture. English is not Mary’s first language, but we have left her letter unedited in order that she can share her story in her own words.

Adjusting to post-secondary school can be tough for any student, but for Indigenous students, the challenges are amplified. Racism, both implicit and explicit, is often an issue, and students have to work hard to overcome these unique challenges. Many schools offer Indigenous students resources to help them succeed, including here at Sheridan College. Our Centre for Indigenous Learning and Support offers a variety of services. We spoke to its Executive Assistant Gillian Kyle about why that’s so important.

LGBTQ Concerns

The LGBTQ community has a suicide rate much higher than the general population. The stigma, prejudice and perceived isolation that LGBTQ youth face can lead to depression and anxiety so extreme that they consider suicide as their only way out. The overlap with Indigenous youth is also alarming: 28 per cent of transgender and Two-Spirit youth have attempted suicide. Organizations like You Can Play and Egale are working to help LGBTQ youth who are struggling with their identities.

Because of the high rate of suicides within the LGBTQ community, many are suffering with issues in mental health that often go unnoticed.

Individuals live in constant fear of being stigmatized or being physically harmed because of who they are.

Transphobia is defined as being discriminatory and prejudiced against transsexual or transgender individuals. Because of this, it’s common for individuals in the LGBTQ community to stay silent about being openly gay or transgender, leading to a multitude of anxieties and depression.

We spoke to Matt Clark, a student at Sheridan College, who identifies as non-binary. This means Matt’s gender falls outside the confines of “male” and “female.” Matt prefers to use they/them pronouns to better reflect their identity, and they spoke to us about their experiences as a transgender youth who has been diagnosed with mental illness.

Coping

There is a clear relationship between mental health and substance abuse in Canadian youth. About one in 25 Ontario students report both elevated psychological distress – that is depression and anxiety – and hazardous drinking.

Around 50 per cent of marijuana users used cannabis to help relieve conditions such as insomnia, depression, and anxiety. There are also prescription drugs dispensed by doctors to help youth cope with their mental illnesses, around 6.5 per cent of youth living in British Columbia, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba were dispensed at least one medication to help with a mood or anxiety disorder.

Post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is the mental and emotional stress that an individual faces after distressing incidents and coping with it can often lead to substance abuse.

While PTSD is often associated with First and Second World War veterans returning home from the horrors of war, it’s become more common among millennials.

Stéphane Grenier, a 29-year old retired veteran of the Canadian military, was diagnosed with PTSD and depression after his tour in Rwanda.

Grenier shares his story at speaking events and believes that there is more to be done in terms of mental health, not only for veterans. He continues to raise awareness by offering peer support to find ways to combat mental health.

Although most individuals correlate PTSD to accidents of war, a study showed that 36 per cent of millennials exhibited PTSD-like symptoms of behaviour rooted in denial, avoidance, and hyper vigilance.

20-year old Phillip French has been newly diagnosed with PTSD following a tragic car accident in September, and has been unable to attend work for more than seven months.

In the video below, Phillip shares his struggles with everyday activities that most 20-year olds take for granted.

That’s the Point

Although thoughts of suicide can seem to be permeating millennial minds, there is hope. Organizations like The Friendship Bench are encouraging discussion about mental health affecting youth.

The Friendship Bench is a not for profit corporation that honours the many selfless acts of Lucas Fiorella, a young man who took his own life due to depression. After his death, his family learned that he would often put effort into making other students who suffer from anxiety or depression feel better just by saying hello. Lucas’s father, Sam Fiorella, is one of the co-founders of the project. He spoke to us about the #YellowIsForHello campaign and why talking about mental health is so important.

Colleges and universities are starting to offer more services to their students and Indigenous communities. Hospitals are improving their mental health facilities for those who need to treatment. Services for youth with mental illnesses are getting better, showing that there is hope for those who are in pain. Below we’ve listed places you can go to for help and some everyday ideas to improve your own mental health.

Kids Help Phone – www.kidshelpphone.ca – 1-800-668-6868

Kids Help Phone – www.kidshelpphone.ca – 1-800-668-6868

Good2Talk – www.good2talk.ca – 1-866-925-5454

Telehealth – 1-866-797-0000

Mental Health Online – www.mentalhealthhelpline.ca – 1-866-531-2600

CAMH – www.camh.ca (Does not provide crisis counselling over phone)

Main Switchboard phone number – 416-535-8501 Toll free – 1-800-463-2338

Mind Your Mind – mindyourmind.ca

CMHA – www.cmha.ca

Here To Help – www.heretohelp.bc.ca

Inkblot – www.inkblottherapy.com

WELLIN5 – www.wellin5.com

E Mental Health – ementalhealth.ca

ConnexOntario – Drug and Alcohol HelpLine – 1800-565-8603

ConnexOntario – Mental health HelpLine – 1-866-531-2600 www.connexontario.ca

Conclusion

In this project we have shown that millennials are clearly struggling with mental health issues, but there are also people working to help. We hope that we’ve included useful stories and resources in initiatives like the Friendship Bench, Partners for Mental Health, and new treatment therapies like virtual reality. There is help and support for those who need it.

In this project we have shown that millennials are clearly struggling with mental health issues, but there are also people working to help. We hope that we’ve included useful stories and resources in initiatives like the Friendship Bench, Partners for Mental Health, and new treatment therapies like virtual reality. There is help and support for those who need it.

This has been a very personal project for our team. Many of us struggle with mental health or know someone who does. We hope this helps you understand what an important issue this is in today’s society.

Our Team

ARINA AMINOVA

JULIA BROWN

TAYLOR CHARETTE

TYLER CHOI

KENNEDY COLTHERD

KASIA HENLEY

CHRISTY JANSSENS

GRANT JENKINS

RENATA KHUZINA

CASSANDRA KING

ISABELLA KRZYKALA

HAILEY MONTGOMERY

SAMANTHA MOYA

NATALIA NAHON

ADITH NATARAJAN

DANIELLE OBAL

PAIGE OGDEN

SAMEREH OSBORNE

CHELSEA OWUSU

CHRISTINA PIPER

COLLEEN PODMOROFF

OLIVIA PULHAM

SAMANTHA RUSSELL

AMELIA SHER

Contact

We'd really love to hear from you so why not drop us an email and we'll get back to you as soon as we can.

Have U Seen This?

According to a health study conducted by Ipsos for Global News, 53 per cent of millennials are at a higher risk of suffering from mental health illnesses, as opposed to 14 per cent of baby boomers.

Media plays a bigger role in millennial mental health than most realize.

We see the same headlines in the media every day: best dressed, worst dressed, most beautiful woman, sexiest man of the year. It’s a constantly updated scroll placing emphasis on physical attributes rather than the individual.

What you don’t see is the need for a positive change.

In this section, we explore how social media, virtual reality, and mass media representations affect mental health in millennials.

Social Media

Canada has a population of approximately 36-million and the Canadian Internet Registration Authority reports that 25.5 million Canadians use the Internet daily. Millennials are consistently using technology as a form of communication, replacing in-person dialogue with multi-channeled screen interaction on things like SnapChat.

We asked a social media expert and one of Sheridan’s counsellors to give their takes on what’s good and bad about social media.

With apps like Instagram, millennials are introduced to a variety of falsehoods, with people often showing only the filtered moments of their lives. The perfect home, the biggest friend group – an image of the “perfect” life. These social media posts create a bubble of loneliness and disconnection. Disconnection from what is true and real.

Platforms like Instagram and Facebook are a way for people to keep in touch with old friends. But, sometimes, millennials find themselves comparing their lives to the progression of their peers, triggering a negative reaction in their mental state, or, even worse, getting caught up in negative social media messages that can have a detrimental effect on people with issues like eating disorders.

Below, we talk to two students about the positives and negatives of social media. Christina tackles the negative aspects of online interaction, while Julia describes how she uses social media as a positive tool to help others struggling with mental health.

An Ipsos study suggests that more than any other age group, millennials are at a higher percentage of being diagnosed with anxiety or depression, and one of the reasons is the constant comparison of themselves to their peers.

On top of feeling inadequate in comparison to their peers, they also may feel ostracized or stigmatized for struggling with mental health.

With the growing use of technology, cyberbullying is on the rise. One in five millennials has been cyberbullied, compared to 15 per cent of younger generations. And according to that report, 41 per cent of millennials who have experience with being cyberbullied suffer from forms of mental health and emotional distress.

Cyberbullying can contribute to mental health issues. Many suffer in silence. Sometimes this can lead to devastating outcomes. Amanda Todd was fifteen when she took her own life. Rehtaeh Parsons was seventeen. Both were victims of cyberbullying. Both saw death as their only escape. What you don’t see is the silent shame and anguish that cyberbullying can have on an individual.

Dealing with issues like cyberbullying can be difficult. It isn’t always done in a healthy way. Stats Canada found that more than 40 per cent of those victimized by cyberbullies had a lower level of trust for others, with 28 per cent of millennials leaving the incident unreported and suffering in silence.

How can we use social media as a tool for positivity to support millennials with mental health issues?

We spoke with Karen McGratten, a psychotherapist who works out of Guelph, Ontario, about the use of social media and how it affects the mental health of millennials. McGratten explained how easy it is to say things on social media that you would never say in person:

McGratten went on to explain that it’s hard to think of consequences when you don’t really see the other person face-to-face and using a public space like social media isn’t the best way to deal with conflict. People who are angry, impulsive, or not thinking rationally in the moment should be careful of the things they say and post as it could be harmful to others or even themselves. According to McGratten:

Media Representation

Media is powerful. It can affect the way mental illnesses are represented and perceived. Often, the negative images projected surrounding those suffering from mental health issues lead others to suffer in silence for fear of being stigmatized and displaced in society.

According to his biography for McGill university, Robert Whitley “is the Principal Investigator of the Social Psychiatry Research and Interest Group at the Douglas Hospital Research Center. He is an assistant professor in the department of psychiatry at McGill University with a focus in recovery and stigma.”

He conducted a study using newspaper articles to focus on the media representations of men versus women through the concept of “the Chivalry Hypothesis” in connection with mental illness.

According to Whitley’s study, the Chivalry Hypothesis refers to the idea that “women are portrayed and treated more leniently and compassionately than men by (male-dominated) juridical institutions and the media even when they have committed a crime of similar nature or magnitude.”

Whitley states that 40 per cent of newspaper articles report crime and violent acts connected with mental illness, compared to less than 20 per cent of articles on the subject of recovery and rehabilitation.

with mental illness, compared to less than 20 per cent of articles on the subject of recovery and rehabilitation.

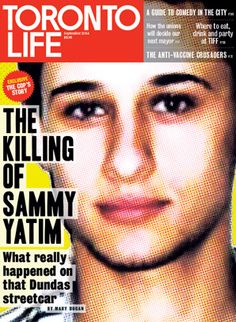

One of the most discussed criminal cases in Ontario was that of 18-year-old Sammy Yatim. He was shot dead on a Toronto streetcar by a police officer, suffering 3 bullet wounds to the chest. A second round of bullets was shot at him when he was already incapable of initiating any physical harm. There were countless reports of the situation and discussion of what actually happened, but many news articles focused on Yatim’s behaviour, specifically, his mental state and descriptions of Yatim’s “erratic behaviour” or “aggressive body language.”

In this sense, Whitley’s hypothesis may connect with the idea that men with mental illness are treated differently in the media in terms of criminal reports.

How do we ensure that further media reporting concerning mental health be written in a way to encourage recovery and therapy instead of supposing the individual is aggressive or violent? We talked to Ryerson University journalism professor Gavin Adamson to find out.

As Adamson discusses above, some media portray those with mental illness in a positive light, others negatively. However, when it comes to films, the one thing they have in common is their inaccuracy. Based on research by Irving Schneider and others, we are able to sort movies into categories and determine whether they are accurate in their portrayal of mental health. However, there is a lot of overlap in the lists that have come out, as the movies may do one thing right, and something else completely wrong. For instance, the person with the mental illness may be depicted accurately, but the portrayal of the illness or “cure” may be wrong. We’ve created an interactive resource of movies that portray mental health, and outline how accurate that portrayal is.

View Profile

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975)

One Flew Over the Cuckoo's Nest (1975)

View Profile

Silence of the Lambs (1991)

Silence of the Lambs (1991)

View Profile

Girl, Interrupted (1999)

Girl, Interrupted (1999)

View Profile

Fight Club (1999)

Fight Club (1999)

View Profile

A Beautiful Mind (2001)

A Beautiful Mind (2001)

View Profile

Black Swan (2010)

Black Swan (2010)

View Profile

Shutter Island (2010)

Shutter Island (2010)

View Profile

Silver Linings Playbook (2012)

Silver Linings Playbook (2012)

View Profile

Split (2017)

Split (2017)

Virtual Reality

Virtual reality is mostly known for intense video game experiences immersing the user into an interactive game. What it’s not obviously known for is being a more common alternative treatment option for mental health illnesses like anxiety or post-traumatic stress disorders. Virtual reality is increasingly being used, as opposed to prescriptions, for those who suffer from mental health illnesses including phobias like a fear of flying, or heights.

Serge Larouche is a psychologist who works with Dr. Stephane Bouchard at the University of Quebec studying virtual reality as therapy.

“Virtual reality exposure is a very useful and efficient tool for the psychologist providing treatment for patients suffering of PTSD. It allows the exposure to be under total control of the client and the therapist,” says Larouche.

This type of therapy is known as cyberpsychology: using exposure therapy to see how the human mind reacts to situations that cause anxiety in the individual. It puts the user in a virtual three-dimensional environment that exposes the user to flashbacks such as war, or a flight simulator in hopes of treating the users’ fear or anxiousness.

“It can be used for specific phobias and also more complex disorders such as panic disorder,” says Larouche.

But how does a person get recommended virtual reality as treatment?

“The doctor would refer the patient to a licensed psychologist; however, exposure therapy requires functional knowledge of learning theory. The doctor would then be well advised to refer the patient to a cognitive behavioural therapist,” says Larouche.

Most patients struggle with costs and what types of treatments are covered by health insurance and if they would be able to afford them.

“If it is provided by a psychiatrist the treatment would be covered by OHIP,” Larouche says, but the cost of psychologists’ fees is not covered by health insurance.

Larouche works at the inVirtuo clinic in Quebec, where the specific rate depends on the psychologist and type of treatment. For example, Oculus is a popular virtual reality headset so the average cost for the headset ranges anywhere between $1200 and $1500.

“Our complete software package (PTSD, panic and agoraphobia, social anxiety, generalized anxiety) costs $5000 plus the cost of a computer powerful enough, about $3000,” says Larouche.

Without OHIP, virtual reality therapy would be near impossible for the average citizen to use as therapy.

“Virtual reality benefits both clients and therapists: most exposure therapies are short term and cost effective. Fear of flying treatment is very costly in traditional exposure but cheap and effective in virtual reality,” says Larouche.

Not having to worry about the cost of treatment and finding an alternative to prescription medication may ease some anxiety in the patient. It is becoming more accessible and a positive form of treatment.

“It is very gratifying to see patients overcome their difficulties quickly and to sometimes see those benefits generalize to other areas of life,” says Larouche.

Although technology often has a way of isolating a person from personal interaction, virtual reality continues to make strides in helping those who suffer with mental health issues to step outside of their comfort zones.

How can we use social media as a tool for positivity so that millennials with issues with mental health don’t suffer in silence?

Mohammad Ghassemi, a doctoral candidate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, is working with professionals to create and launch technology that focus on helping individuals get immediate access and helpful tips from a mental health professional. It’s a wearable watch with voice detection that uses specific algorithms to distinguish the tone of the conversation.

We spoke with Ghassemi to see how techs and mental health professionals can work together to improve mental health therapy.